The Object Model (oM): define new objects¶

This section introduces the BHoMObject, which is the foundational class for most of the Objects found in BHoM.

We also introduce the IObject, the base interface for everything in BHoM.

BHoMObject Code Structure and Content¶

A typical BHoM object definition is given simply by defining a class with some public properties. That's it! No constructors or anything needed here.

Here is an example of what a BHoM object definition looks like:

using BH.oM.Base;

using BH.oM.Geometry;

namespace BH.oM.Acoustic

{

public class Speaker : BHoMObject

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Properties ****/

/***************************************************/

public Point Position { get; set; } = new Point();

public Vector Direction { get; set; } = new Vector();

public string Category { get; set; } = "";

/***************************************************/

}

}

In general, most classes defined in BHoM are a BHoM object, except particular cases.

Among these exceptions, you can find Geometry and Result types.

The reason for this is both conceptual and to aid performance. Geometries and Results are not "objects" in the strict sense of the term. In addition, separating those types from actual BHoMObject objects greatly helps with performance down the line.

Inheritance from BHoMObject¶

Note that the name of a class in a new object definition is followed by : BHoMObject. This is to say that this object inherits from BHoMObject. This is important if you want your new class to benefit from the properties and functionalities a BHoM object provides.

Here is a part of the BHoMObject class definition:

namespace BH.oM.Base

{

public class BHoMObject : IObject

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Properties ****/

/***************************************************/

public Guid BHoM_Guid { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public string Name { get; set; } = "";

public HashSet<string> Tags { get; set; } = new HashSet<string>();

public Dictionary<string, object> CustomData { get; set; } = new Dictionary<string, object>();

}

}

As you can see, the BHoMObject only contains a set of properties.

As for any other class in the BHoM framework, we try to keep behaviour (functions, methods) and properties separated. Minor exceptions to this separation are seldom made for for practical efficiency and technical reasons.

The functionalities of the BHoMObject, as well as of the other BHoM framework types, are defined in the BHoM_Engine.

Everything is an IObject¶

As we said before, not everything is an BHoMObject: exceptions are Geometry and Results objects.

However, in order to easily identify all the types coming from the BHoM framework, a basic type, or interface, is needed.

That's why everything is defined to be an IObject at its root. All BHoM objects will always be an IObject, as BHoMObject is itself inheriting from IObject. Everything else will be too through the chain of interfaces.

Let's have a look at one of the Geometry objects, Pipe. As you can see, it inherits from ISurface, one of the base Geometry types.

namespace BH.oM.Geometry

{

public class Pipe : ISurface

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Properties ****/

/***************************************************/

public ICurve Centreline { get; set; } = new Line();

public double Radius { get; set; } = 0;

public bool Capped { get; set; } = true;

/***************************************************/

}

}

The interface ISurface inherits from another interface, IGeometry:

IGeometry inherits from IObject, which as we said will always be the top-level of any type defined in the BHoM framework:

Defining Properties¶

Properties correspond to the information you need to define your object (to the exception of the properties the BHoMObject class already provides). A few things to keep in mind when you create those:

- All properties must be public and have a public get and set methods, written

{get; set;}. (This means thatreadonlyproperties are not directly allowed - see paragraph below "Immutable Objects" if you want to know more). - Make sure you provide a default value X for your properties by using

= X;at the end of their definition; If a properties is too complex to be defined that way, simply set it to null (write= null;at the end). - Property names should not contain redundant information, for example, repeating the type of the property in its name. A property of type

Nodefor example should not haveNodein the property name unless it is the only name of the property. E.G. a property set up asNode StartNodeshould only be calledStart, as theNodeelement comes from the property type - the better implementation of this isNode Start. This prevents duplication of information in the properties.

As objects grow in complexity, it is useful to think in terms of splitting an object's properties into categories:

-

Object Defining properties. The minimal required information you need to construct the full object. These should generally be the properties of the objects defined in the BHoM

-

Derived properties. Any property that could be calculated from the other properties. These should generally be handled by the BHoM_Engine using extension methods. This choice allows to calculate and obtain those properties only when needed; however, it also mean that you will have to write an explicit "get" method that users will be able to access through the dot

.accessor. -

Software specific properties such as Software IDs, etc. To ensure that the BHoM is software agnostic, we resorted to store this information in a dynamic (not statically typed) way. That's why we're using a

Dictionary(list of key-value pairs) property of the BHoMObject calledCustomData. For example, the ID assigned to an object for a certain software will be stored as a value of the KeysoftwareName_id. -

Results from analysis. These are to be generally stored as a completely different set of classes, as you can have thousands of results per object.

As an example between Defining and Derived properties for geometry: A line is defined by two points. These two points are properties of the line (category 1). A line can also have a length, but as that can be derived from the points, this instead sits in the BHoM_Engine as a method called "Length()" (category 2). This structure makes sure that on update of the points, the length will also be updated ensuring compatibility of properties at all times.

Defining Constructors and Local Methods¶

Important: To the exception of Immutable Objects, BHoM objects should never have a constructor. In general, there should be no method defined in the class either (see Casting methods). So, ultimately, a BHoM object is really nothing more than a list of properties and their default values. Objects will be created either by using an Object Initialiser or via a Create method from the Engine.

Anything that manipulates data should generally be in the BHoM Engine. That being said, there are rare occasions where you will see a local method written directly in the object definition. Those methods are generally created there for optimisation reasons or because of the constraints of C# and are therefore the exception, not the rule.

For those of you coming from object oriented programming, it might seems quite unnatural to take functionality outside a class as much as possible. There is a few reasons why we have gone that direction:

- Properties of an object are unlikely to change frequently and it is reasonable to expect a list of properties to converge quickly to a final solution, never to be touched again. The methods, on the other hand are always growing, improving or being debugged. Keeping them in more isolated packages will reduce the impact of their change.

- We want as many people to be able to contribute as possible. While not everyone will be able to write complex algorithms, we expect every engineer to be able to define what properties should be found in an object he/she is using regularly. By separating the complexity levels in different repos, people are enabled to participate by focusing on the part they are comfortable with.

- Some of the contributors to the BHoM might wish to keep a few methods and algorithms related to a BHoM object private. By limiting the BHoM to object definitions, we are making it easier to share the object models without being forced to share anything else. Do not worry though, the Engine already contains plenty of useful methods and is constantly growing.

The main disadvantage is that the hierarchical structure of the repositories makes mandatory to update/rebuild any other repository that comes down. For example, any change to the BHoM repository means there is large ripple effect on nearly every other repository.

Namespace and Folder Structure¶

- BHoM objects are organised as shown in the image below. All analytical objects are stored in their respective discipline project (e.g. Structure, Environment,...).

- A Common project is user for objects shared between disciplines.

- The inter-disciplinary representation is expressed through physical objects (stored in the Physical folder).

- Finally, the BHoM and Geometry folders contain core objects and geometry definitions respectively.

Namespaces have to match the folder structure.

In the rare case where folders are more than 3 levels deep, the namespaces are allowed to stop there. For example, the BH.oM.Structure.Results folder contains subfolders. Objects defined in those subfolders are allowed to use the namespace BH.oM.Structure.Results instead of BH.oM.Structure.Results.SubFolder.

Immutable Objects¶

Warning: This is more advanced feature and not necessary in 99% of the case so you can safely skip this.

For some rare objects, it would be problematic to keep only the Defining properties. That is generally the case if the Derived properties are very expensive to compute. In that case, those objects should inherit from the IImutable interface. This is explicitly stating that the properties of those objects should not be modified as it would create inconsistencies within the object. In that case, the properties that are overlapping would only have a { get; } accessor instead of the usual { get; set; }. Here's an example of such a class (with some skipped section highlighted as ...)

public class CableSection : BHoMObject, ISectionProperty, IImmutable

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Properties ****/

/***************************************************/

public Material Material { get; set; } = null;

/***************************************************/

/**** Properties - Section dimensions ****/

/***************************************************/

public int NumberOfCables { get; } = 0;

public double CableDiameter { get; } = 0;

public CableType CableType { get; } = CableType.FullLockedCoil;

public double BreakingLoad { get; }

...

/***************************************************/

/**** Constructors ****/

/***************************************************/

public CableSection(...)

{

...

}

/***************************************************/

}

Apart from the use of { get; } instead of { get; set; }, you will notice that IImmutable objects will have to define their own constructors inside the class. This is because Object Initialiser do not work on properties without a set so we cannot simply define the constructors in the Engine as we usually do.

Casting Methods¶

Warning: This is more advanced feature and not necessary in 99% of the case so you can safely skip this.

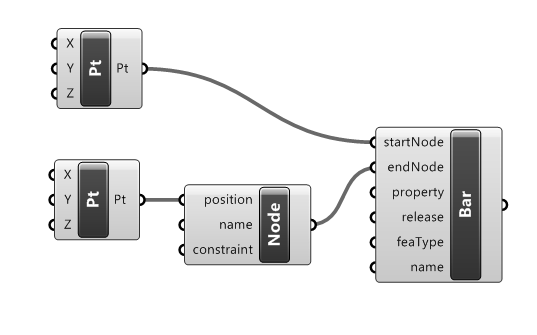

It is convenient for some objects to be able to be casted from something else. For Example, a geometrical Point could be casted from a Vector or a structural Node could be casted from a Point. This is especially useful inside a user interface. Here's an example where this case is relevant:

public class Node : BHoMObject

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Properties ****/

/***************************************************/

public Point Position { get; set; } = new Point();

public Constraint6DOF Constraint { get; set; } = null;

/***************************************************/

/**** Explicit Casting ****/

/***************************************************/

public static explicit operator Node(Point point)

{

return new Node { Position = point };

}

/***************************************************/

}

Unfortunately, C# doesn't allow to define this outside the class so we have no choice but to do it in the BHoM. Be mindful that this is only relevant when an object could be created from a single other element so this only apply in unique cases and shouldn't be defined in every class.