What is the BHoM Engine?¶

The BHoM Engine repository contains all the functions and algorithms that process BHoM objects.

As we saw in the introduction to the Object Model, this structure gives us a few advantages, in particular:

- we can see the BHoM object as a list of properties and their default values;

- in the same way, the BHoM Engine can be seen as a big collection of functions.

Repo Structure¶

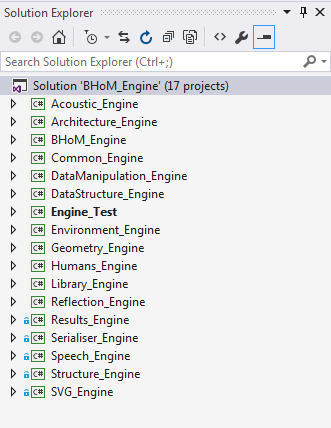

The BH.Engine repository is structured to reflect this strategy. The Visual Studio Solution contains several different Projects:

Each of those projects takes care of a different type of functionality. The "main" project however is the BHoM_Engine project: this contains everything that allows for basic direct processing of BHoM objects. The other projects are designed around a set of algorithms focused on a specific area such as geometry, form finding, model laundry or even a given discipline such as structure.

Why so many projects?

The main reason why the BHoM Engine is split in so many projects is to allow for a large number of people to be able to work simultaneously on different parts of the code.

Keep in mind that every time a file is added, deleted or even moved, this changes the project file itself. Consequentially, submitting code to GitHub can become really painful when multiple people have modified the same files.

Splitting code per project therefore limits the need to coordinate changes to the level of each focus group.

Another benefit will be visible when we get to the "Toolkit" level: having different project makes it easier to manage Namespaces and make certain functionalities "extendable" in other parts of the code, such as in Toolkits.

Folder structure¶

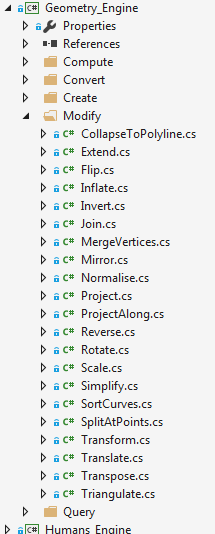

If we look inside each Engine project, we can see that there are some folders. Those folders help categorize the code into specific actions.

There are five possible action types that correspond to five different folder names: Compute, Convert, Create, Modify, and Query.

Let's consider the Geometry_Engine project; we can see that it contains all of those folders:

Those five action names should be the same in all projects; however it's not mandatory that an Engine project should have all of them.

Each folder contains C# files; those files must be named as the target of this action.

Engine method types¶

In order to sort methods and organise them, 5 different categories of Engine methods exist. All methods will fall into one of these categories.

- Create: methods that instantiate a new object. Remember that the Objects are simple classes defined with no constructor (unless they must be

IImmutable-- the only exception where constructors are allowed). You can define any number of methods that create the same objects via any combination of input parameters. - Modify: methods that modify an object. Generally, the modify method should have a return type that is of the same type of its first argument. This is to state that the method effectively returns a modified copy of the input object.

- Query: methods that return some derived value from the input object. A derived value is something that is not found among the defining properties of the object, but that can be inferred from them. For example, the length of a Line object, if the Line itself is defined only by its start and end point.

- Convert: methods that transform the input object into another type that has similar, or equivalent, meaning. For example, converting a BHoM Structural Bar into a Robot Bar.

- Compute: methods that perform some computational or I/O heavy functionality, or which do not fall into any other of the previous categories.

If you are in doubt, try finding another file that does a similar thing in another project, and see where that is placed.

For example, in the Geometry_Engine project there is a Query folder that contains, among others, a Length.cs file. This file contains methods that take care of Querying the Length for geometric objects. Consider that another equally named Length.cs file might be present in the Query folder of other Engine projects; this is the case, for example, of the Structure_Engine project, where the file contains method to compute the link of Bars (structural objects).

File Structure¶

The file is structured in a slightly unusual way for people used to classic object-oriented programming, so let's look at an example. The following is an extract from the ClosestPoint.cs file of the Geometry_Engine project.

namespace BH.Engine.Geometry

{

public static partial class Query

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Public Methods - Vectors ****/

/***************************************************/

public static Point ClosestPoint(this Point pt, Point point) {...}

/***************************************************/

public static Point ClosestPoint(this Vector vector, Point point) {...}

/***************************************************/

public static Point ClosestPoint(this Plane plane, Point point) {...}

/***************************************************/

/**** Public Methods - Curves ****/

/***************************************************/

public static Point ClosestPoint(this Arc arc, Point point) {...}

/***************************************************/

public static Point ClosestPoint(this Circle circle, Point point) {...}

/***************************************************/

...

}

}

A few things should be noted:

-

The Namespace always starts with

BH.Enginefollowed by the project name (without the suffix "__Engine_", obviously). -

The file should contain one and only one class, named like the containing folder. For example, any C# file contained in the "Query" folder will contain only one class called

Query. -

Consequently, the name of the file itself will not correspond to the name of the class, as it is usually recommended in Object Oriented Programming. The file name will generally only reflect the name of the methods defined in it.

-

Note that the class is declared as a partial class. Also note that the class is declared as static.

Static and partial

The last point might be a bit cryptic for those that are not fluent in C#. Here is a brief explanation that should be enough to move on the next topics.

static means that the content of the class is available without the need to create (instantiate) an object of that class. However, that requires that all the functions contained in the class are declared static as well.

On the other hand, partial means that the full content of that class can be spread between multiple files.

Having the engine action classes declared as static and partial helps us simplifying the structure of the code and expose only the relevant bits to the average contributors.

Class Structure¶

Fluent C# users should have no problem understanding the structure of Engine classes.

For those that want to get stuck without too many technical details, here are a few instructions on how to edit the action classes.

- Inside the class, create a function for each type of object you want to be able to handle. Notice that all the methods have the same name and possibly additional parameters, the only difference is the type of the first argument and possibly the return type.

- Write this in front of the first argument of each function. This will for example allow to call the methods shown above using the dot

.notation. For example, if you have an instance of anArctype calledmyArc, you will be able to domyArc.ClosestPoint(refPoint). This way of defining functions is called Extension Methods and will be better explained below. - If you find yourself typing the same code for multiple functions (or even inside the same function), you can still create private static methods. Just make sure you place them in a separate private section (use same 3 line comment) after the public methods. In rare cases, you might also want to have your own private data structure for convenience. If that data structure will never be used elsewhere, just define it at the end of the class.

namespace BH.Engine.Geometry

{

public static partial class Modify

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Public Methods ****/

/***************************************************/

public static Mesh MergeVertices(this Mesh mesh, double tolerance = 0.001) //TODO: use the point matrix {...}

/***************************************************/

/**** Private Methods ****/

/***************************************************/

private static void SetFaceIndex(List<Face> faces, int from, int to) {...}

/***************************************************/

/**** Private Definitions ****/

/***************************************************/

private struct VertexIndex {...}

}

}

Advanced topics

While you might be able to write code in the BHoM Engine for a time without needing more than what has been explained so far, you should try to read the rest of the page.

The concepts presented below are a bit more advanced; if you follow them, however, you will be able to provide a better experience to those using your code. Knowing what Polymorphism is and what the C#dynamictype is will also likely get you out of problematic situations, especially when you are using code from people that have not read the rest of this page.

Extension Methods¶

A concept that is very useful in order to improve the use of your methods is the concept of extension methods. You can see on the example code below that we get the bounding box of a set of mesh vertices (i.e. a List of Points) by calling mesh.Vertices.Bounds(). Obviously, the List class doesn't have a Bounds method defined in it. The same goes for the BHoM objects; they even don't contain any method at all. The definition of the Bound method is actually in the BHoM Engine. In order for any BHoM objects (and even a List) to be able to call self.Bounds(), we use extension methods. Those are basically injecting functionality into an object from the outside. Let's look into how they work:

namespace BH.Engine.Geometry

{

public static partial class Query

{

...

/***************************************************/

/**** public Methods - Others ****/

/***************************************************/

public static BoundingBox Bounds(this List<Point> pts) {...}

/***************************************************/

public static BoundingBox Bounds(this Mesh mesh)

{

return mesh.Vertices.Bounds();

}

/***************************************************/

...

}

}

Here is the properties of the Mesh object for reference:

namespace BH.oM.Geometry

{

public class Mesh : IBHoMGeometry

{

/***************************************************/

/**** Properties ****/

/***************************************************/

public List<Point> Vertices { get; set; } = new List<Point>();

public List<Face> Faces { get; set; } = new List<Face>();

/***************************************************/

/**** Constructors ****/

/***************************************************/

...

}

}

Notice how each method has a this in front of their first parameter. This is all that is needed for a static method to become an extension method. Note that we can still calculate the bounding box of a geometry by calling BH.Engine.Geometry.Query.Bounds(geom) instead of geom.Bounds() but this is far more cumbersome.

To be complete, we should also mention that we could simply call Query.Bounds(geom) as long as using BH.Engine.Geometry is defined at the top of the file.

Polymorphism¶

While not completely necessary to be able to write methods for the BHoM Engine, Polymorphism is still a very important concept to understand. Consider the case where we have a list of objects and we want to calculate the bounding box of each of them. We want to be able to call Bounds() on each of those object without having to know what they are. More concretely, let's consider we want to calculate the bounding box of a polycurve. In order to do so, we need to first calculate the bounding box of each of its sub-curve but we don't know their type other that it is a form of curve (i.e. line, arc, nurbs curve,...). Note that ICurve is the interface common to all the curves.

namespace BH.Engine.Geometry

{

public static partial class Query

{

...

/***************************************************/

public static BoundingBox Bounds(this PolyCurve curve)

{

List<ICurve> curves = curve.Curves;

if (curves.Count == 0)

return null;

BoundingBox box = Bounds(curves[0] as dynamic);

for (int i = 1; i < curves.Count; i++)

box += Bounds(curves[i] as dynamic);

return box;

}

/***************************************************/

...

}

}

Polymorphism, as defined by Wikipedia, is the provision of a single interface to entities of different types. This means that if we had a method Bounds(ICurve curve) defined somewhere, thanks to polymorphism, we could pass it any type of curve that inherits from the interface ICurve.

The other way around doesn't work though. If you have a series of methods implementing Bounds() for every possible ICurve, you cannot call Bounds(ICurve curve) and expect it to work since C# has no way of making sure that all the objects inheriting from ICurve will have the corresponding method. In order to ask C# to trust you on this one, you use the keyword dynamic as shown on the example above. This tells C# to figure out the real type of the ICurve during execution and call the corresponding method.

Polymorphic Extension Methods¶

Alright. Let's summarize what we have learnt from the last two sections:

-

Using method overloading (all methods of the same name taking different input types), we don't need a different name for each argument type. So for example, calling Bounds(obj) will always work as long as there is a Bounds methods accepting the type of obj as first argument.

-

Thanks to extension methods, we can choose to call a method like Bound by either calling Query.Bounds(obj) or obj.Bounds().

-

Thanks to the

dynamictype, we can call a method providing an interface type that has not been explicitly covered by a method definition. For example, We can call Bounds on an ICurve even if Bounds(ICurve) is not defined.

Great! We are still missing one case though: what if we want to call obj.Bounds() when obj is an ICurve? So on the example of the PolyCurve provided above, what if we wanted to replace

withBut why? We have a perfectly valid way to call Bounds on an ICurve already with the first solution. Why the need for another way? Same thing as for the extention methods: it is more compact and being able to have auto-completion after the dot is very convenient when you don't know/remember the methods available.

So if you want to be really nice to the people using your methods, there is a solution for you:

namespace BH.Engine.Geometry

{

public static partial class Query

{

...

/***************************************************/

/**** Public Methods - Interfaces ****/

/***************************************************/

public static BoundingBox IBounds(this IBHoMGeometry geometry)

{

return Bounds(geometry as dynamic);

}

}

}

If you add this code at the end of your class, this code will now work:

Two comments on that: - We used IBHoMGeometry here because every geometry implements Bounds, not just the ICurves. ICurve being a IBHoMGeometry, it will get access to IBounds(). (Read the section on polymorphism again if that is not clear to you why). In the case of a method X only supporting curves such as StartPoint for example, our interface method will simply be StartPoint(ICurve). - The "I" in front of IBounds() is VERY IMPORTANT. If you simply call that method Bounds, it will have same name as the other methods with specific type. Say you call this method with a geometry that doesn't have a corresponding Bounds method implemented so the only one match is Bounds(IBHoMGeometry). In that case, Bounds(IBHoMGeometry) will call itself after the conversion to dynamic. You therefore end up with an infinite loop of the method calling itself.

PS: before anyone asks, using ((dynamic)curve).Bounds(); is not an option. Not only it crashes at run-time (dynamic and extension methods are not supported together in C#), it will not provides you with the auto completion you are looking for since the real type cannot be know statically.

Fallback Methods¶

But what if we do not have a method implemented for every type that that can be dynamically called by IBounds? That is what private fallback methods are for. In general fallback methods are used for handling unexpected behaviours of main method. In this case it should log an error with a proper message (see Handling Exceptional Events for more information) and return null or NaN.

namespace BH.Engine.Geometry

{

public static partial class Query

{

...

/***************************************************/

/**** Private Methods - Fallback ****/

/***************************************************/

private static BoundingBox Bounds(IGeometry geometry)

{

Reflection.Compute.RecordError($"Bounds is not implemented for IGeometry of type: {geometry.GetType().Name}.");

return null;

}

/***************************************************/

...

}

}

Being private and having an interface as the input prevents it from being accidentally called. It will be triggerd only if IBounds() couldn't find a proper method for the input type.

Additional comment:

- At this moment BHoM does not handle nullable booleans. This means it is impossible to return null from a bool method. In such cases fallback methods can throw [NotImplementedException].

What About Execution Speed ?¶

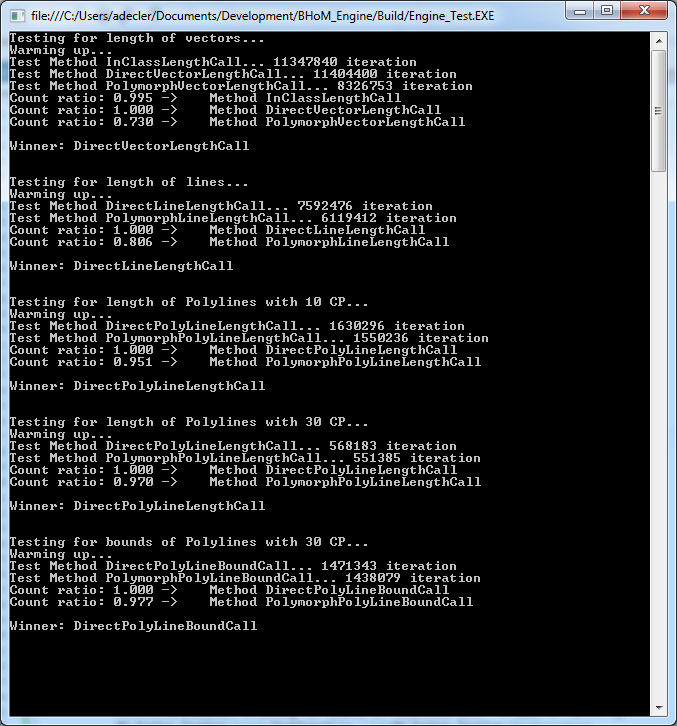

For the most experienced developers among you, some might worried about execution speed of this solution. Indeed, we are not only using extension methods but also the conversion to a dynamic object. This approach means that every method call of objects represented by an interface is actually translated into two (call to the public polymorphic methods and then to the private specific one).

Thankfully, tests have shown that efficiency lost is minimal even for the smallest functions. Even a method that calculates the length of a vector (1 square root, 3 multiplications and 2 additions) is running at about 75% of the speed, which is perfectly acceptable. As soon as the method become bigger, the difference becomes negligible. Even a method as light as calculating the length of a short polyline doesn't show more than a few % in speed difference.

RunExtensionMethod Pattern¶

The concept of polymorphic extension methods explained above has one serious limitation: it works only if all methods aimed to be called by the dynamically cast object are contained within one class. That is not the case e.g. for Geometry method, which is divided into a series of Query classes spread across discipline-specific namespaces: BH.Engine.Structure, BH.Engine.Geometry etc. To enable IGeometry method, a special pattern based on RunExtensionMethod needs to be applied:

namespace BH.Engine.Spatial

{

public static partial class Query

{

/******************************************/

/**** IElement0D ****/

/******************************************/

[Description("Queries the defining geometrical object which all spatial operations will act on.")]

[Input("element0D", "The IElement0D to get the defining geometry from.")]

[Output("point", "The IElement0Ds base geometrical point object.")]

public static Point IGeometry(this IElement0D element0D)

{

return Reflection.Compute.RunExtensionMethod(element0D, "Geometry") as Point;

}

/******************************************/

}

}

RunExtensionMethod method is a Reflection-based mechanism that runs the extension method relevant to type of the argument, regardless the class in which that actual method is implemented. In the case above, IGeometry method belongs to BH.Engine.Spatial.Query class, while e.g. the method for BH.oM.Geometry.Point (which implements IElement0D interface) would be in BH.Engine.Geometry.Query - thanks to calling RunExtensionMethod instead of dynamic casting it can be called successfully. The next code snippet shows the same mechanism for methods with more than one input argument (in this case being an IElement0D to be modified and a Point to overwrite the geometry of the former).

namespace BH.Engine.Spatial

{

public static partial class Modify

{

/******************************************/

/**** IElement0D ****/

/******************************************/

[Description("Modifies the geometry of a IElement0D to be the provided point's. The IElement0Ds other properties are unaffected.")]

[Input("element0D", "The IElement0D to modify the geometry of.")]

[Input("point", "The new point geometry for the IElement0D.")]

[Output("element0D", "A IElement0D with the properties of 'element0D' and the location of 'point'.")]

public static IElement0D ISetGeometry(this IElement0D element0D, Point point)

{

return Reflection.Compute.RunExtensionMethod(element0D, "SetGeometry", new object[] { point }) as IElement0D;

}

/******************************************/

}

}

Naturally, in order to enable the use of RunExtensionMethod pattern by a given type, a correctly named extension method taking argument of such type needs to be implemented.